-7000

The Mayan Economy

How the Mayans built up their super-stable economy over thousands of years.

The Mayan civilisation was a not an empire in the usual sense, but a combined network of cities and communities located in the area central America, between Mexico and Colombia, mostly concentrated in modern-day Honduras and Nicaragua. It could be the longest-ever civilisation, dating from as early back as 7,000 BCE all the way up until to the 16th century CE, although there are still many descendants living on that land today, farming as as they did back then. Some of the main cities at their peak had tens of thousands of inhabitants and this takes an economic strategy in order to not only run smoothly, but to last as long as they did. Though the Ancient Maya were never technically united under one single ruler, each of their states had its own central government, with a king as its main ruler, but they shared common interests through both ideology and trade.

The Mayans did not have money in the modern sense, as they did not have a central government-issued currency, instead they used commodities and trade to structure their long-lasting civilisation. Over many millennia the Mayans grew from small self-sustaining families and villages to huge cities, and with that came the necessary advances in their economy. Their economy had a basic two-tier structure of subsistence and luxury items. Subsistence items consisted of things that people would need to live on from day to day, such as food, clothing, pots and tools, whereas luxury items included jewellery, precious stones, gold, copper, fancy clothing, art and sculptures.

While barter was the main form of trade early on, as the population grew and farmers began to produce more than they needed for their family, they wanted to trade for things with others, outside of their own village. So eventually they started organising communal trade gatherings at a central location and on certain days to make it easier for people to do business with each other. As these markets grew, they needed some consistency, so the local leader would set rules for the market under their jurisdiction, including a common value for the commodities - which could vary between different markets in different areas, but stayed the same within the same market, as the prices would be guided to supply and demand, relative to how far the goods on offer were from their original source – i.e. locally grown or hand-made produce would be cheaper than produce that had been brought in from farther afield.

The large Mayan cities would have correspondingly large markets, and as the city was under a central ruler, the markets had rules to govern all within its borders. While they would still be subject to the same supply and demand format as smaller markets, the size of these larger markets and the population they served, meant more people would bring in produce from outside of the local state, and even from lands outside of the entire Mayan civilisation. Many rulers put a tax on their markets, some of the collected tax would be passed down to the poorest in society to appease them and keep society settled, the rest of the tax would be used to fund the city and no doubt for for their own personal wealth.

Although most subsistence items were priced depending on supply and demand, some of them were in fact used as a basic form of currency. For example, archaeologists have found evidence that both salt and cocoa beans have been been used in such a way, people could trade their goods for cocoa beans or salt and then subsequently use those to trade with other people for the goods they wanted, whether at the same market, or different market one, potentially even from state to state. This enabled people to produce surplus items for sale and trade them with people who wanted them without offering anything they wanted in return – the very core concept of money. With city rulers, or their advisors and economists, setting the rules, taxes and prices in markets based on Mayan-trade economics used interchangeably throughout the Mayan states, even without a central currency, the commodities themselves could be used in place of money – holding their intrinsic value to enable a free-flowing economy, with minimal input from the governments.

While distance played its part in how goods were priced, this could be exploited by traders hoping to turn a profit by buying goods cheaper from a source distant from a city, carrying it by both canoe and foot, without help from animals to bear the load, they could sell it at a profit. Mayans travelled as far as the Cuba and Cancun in Mexico to trade common Mayan goods, such as cocoa beans, salt and high-quality hand-made items, such as pots, which were highly sought after and they would bring back things such as gold and luxury items to trade in Mayan cities. This helped grow the overall Mayan economy and ensured a bustling market economy, with goods both coming in and going out of the cities for profit, but within the local society commodity prices remained more stable.

Government-issued money might seem like the best way to run an economy-based society, it might even seem like the only way to many people, but the Mayan civilisation, which ran for far longer than any other civilisation and had no central ruler, proves otherwise, they managed just fine and in fact flourished without it. Commodity trading on an individual scale worked, subsistence items were in strong supply and fair markets gave both a level-playing field and happier society by ensuring everyone actually played a role that was contributing to the economy. Their commodity-based economy worked on a civilisation level too, it ensured stability to never before or since seen levels of longevity, encouraged international trade, and allowed them to create wonderful cities, and their astronomy and mathematical skills were unmatched.

The Mayans had 3 main classes, from the farmers at the bottom who made up the bulk of the population, to the middle class made up of the artisans, skilled tradespeople, traders, mathematicians, astronomers and advisors, with kings and rulers at the top. This was all interwoven into an entirely commodity-based economy, which because it was built upon a foundation of location-relative supply and demand, is far more beneficial to the overall society and one can imagine made it almost impossible for the gap in wealth between the 3 classes to be anywhere near as vast as it is today.

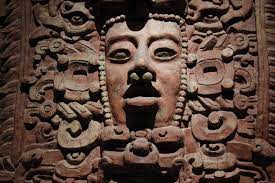

Seeing how intricate they were able to carve materials, it is somewhat surprising that they never created money in the form of government-issued money, maybe it was because nobody would of accepted anything without intrinsic value as they could just trade what they had with someone else; that they were too concerned about forgery; they were worried hoarding of wealth would lead to the removal of skilled workers and their families from needing to work and contribute to society directly; or maybe they didn’t go for it for another reason. Sometimes if it ain’t broke, (and it has lasted thousand of years), it doesn’t need fixing, especially not by replacing money from something of tangible value with pure imagination.